Long before ballots were cast and parliaments built, political protest in Australia was forged in chains by the men and women banished here.

A new digital exhibition explores how the nation’s earliest convicts were not simply passive victims of a brutal penal system but among Australia’s first political demonstrators - organised, ideological and prepared to resist what they saw as unjust.

Unshackled: The True Convict Story has launched at the UNESCO-listed Woolmers Estate in northern Tasmania, bringing together newly digitised records, historical research and immersive storytelling to recast the role of convicts in shaping Australia’s democratic traditions.

Led by Monash University academics, the exhibition contends transportation to Australia functioned as a tool of political repression across the British Empire, sweeping up rebels, radicals and reformers alongside petty criminals.

In so doing, it exported unrest to the colonies.

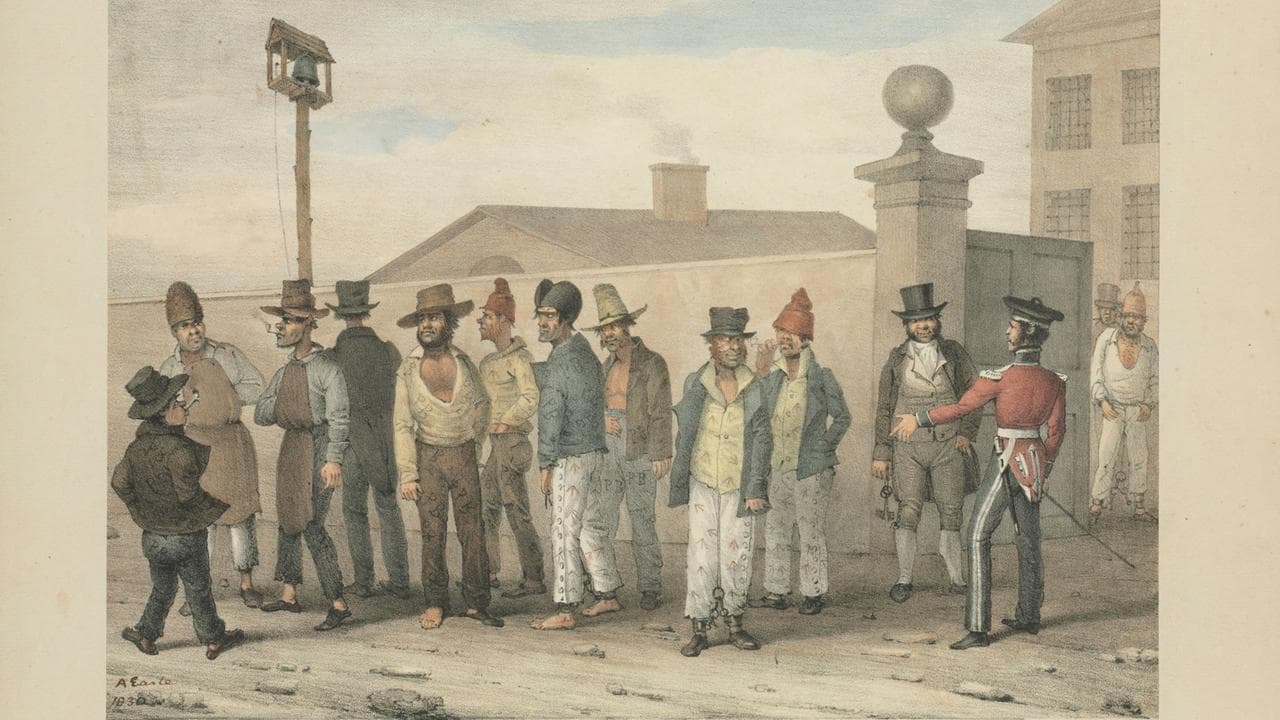

Resistance was a defining feature of convict life from the earliest days of settlement, says Associate Professor Tony Moore in one of the exhibition's films.

“Rebellions by the United Irish convicts at Castle Hill in 1804 and the Eureka Stockade rebellion in 1854 are linked by the battle cry ‘Death or Liberty’,” Dr Moore says.

“They both show a preparedness to resist unfair treatment and unfair rules by which people were governed.”

The exhibition investigates those uprisings within a broader pattern of protest, ranging from organised revolts, work stoppages and hunger strikes to mass absconding, all the while arguing no punishments metered out could extinguish collective action.

“Irish prisoners were not prepared to simply be victims of passive or overt cruelty … in fact they took it into their own hands to resist,” Dr Moore says.

Those who challenged authority faced harsh reprisals under a system designed to crush resistance, as one first hand account describes.

"Two dozen lashes - which was a light sentence - always left the victim's back a jelly of bruised flesh and congealed blood," the video describes.

"A pool of blood and a piece of flesh were no uncommon sight after two dozen had been flogged."

One of the figures investigated in the exhibition is Phillip Cunningham, a veteran of the failed United Irish uprising of 1798 transported to NSW after being convicted of sedition.

In 1804, Cunningham emerged as a leader of the Castle Hill rebellion, as convicts seized weapons in Sydney’s northwest and planned to march on Parramatta and Port Jackson, echoing tactics used during the Irish revolt.

The uprising was betrayed and crushed by the NSW Corps, prompting the first declaration of martial law in Australia’s history.

Cunningham was hanged and his body left on display as a warning to others - an early example of how colonial authorities responded to organised dissent.

Rebellion wasn't the original aim of many transported radicals, according to senior lecturer and oral historian Maura Cronin.

“The reality of open rebellion was something that almost came as a surprise in the late 1790s,” Dr Cronin says about the lead-up to the Castle Hill episode.

“The United Irishmen had originally intended to meet their aims through political means (but) they were going nowhere.”

The exhibition looks at convict resistance within the international context of imperialism, tracing unrest driven by political exclusion, economic upheaval and land dispossession across Britain and Ireland before examining how those forces were intensified in colonial Australia.

It also explores the intersection between the convict system and frontier violence, arguing that transported labour was central to the dispossession of First Nations people.

At the same time, the exhibition highlights instances of co-operation and solidarity between Aboriginal people and European convicts in the early decades of settlement.

More than 160,000 convicts were transported to Australia, including at least 3600 political prisoners convicted for protest, unionism, media freedom and resistance to imperial rule.

The project’s researchers argue that the politically active convicts contributed profoundly to advances in democratic and workplace rights in Australia and abroad.

While the exhibition avoids drawing direct lines between past and present, its creators say revisiting Australia’s convict story offers context for contemporary debates about protest, punishment and state power.

Around the world, political demonstrations - some peaceful, others violently suppressed - continue to test the limits of authority, from the mass protests in Iran to deaths of protesters on the streets of the US.

The exhibition suggests resistance rather than compliance has often been a catalyst for political change, even when met with overwhelming force.

Novelist Thomas Keneally, who appears in the exhibition’s video material, offers a more reflective reading of the transported Irish rebels.

“I look at those United Irishmen in early NSW as - despite their drinking habits - angels of enlightenment," he says.

"This was not a bad set of forebears to lay down for an Australian populace.”

The exhibition’s creators stress that Unshackled is not about romanticising violence or rebellion but expanding a national narrative that has long framed convicts as either victims or villains.

Instead, they argue, Australia’s democratic culture was shaped in part by people who challenged authority under extreme constraint.

It's surely a legacy that complicates the nation’s understanding of protest, dissent and political participation.