When no-fault divorce was introduced in the 1970s, thousands of Australians queued outside the Family Court to cement their break-ups.

The bold Whitlam government reform, which also established the court itself, reshaped how the law dealt with intimate partner disputes and made child welfare paramount in all decisions.

It also swamped judges and lawyers with work.

Former chief justice Diana Bryant, who presided over the court between 2004 and 2017, remembers it as an exciting time to be a lawyer specialising in the field.

"People on day one were lining up to get divorces, there were views of people lining up outside the court," she tells AAP.

"The interesting part for me was that you could make all sorts of arguments in accordance with the Family Law Act because it was new legislation.

"There were no precedents or cases you could follow ... every case was potentially making new law."

But the reaction to the reforms were mixed.

"Everything was about the best interests of children and in relation to property settlements, all contributions were taken into account, even non-financial contributions as a parent," Ms Bryant says.

"Women definitely came out of it well, as they should have.

"But that meant there were a number of men disgruntled with the Act and the decisions being handed down."

Leonard John Warwick, who waged a murderous campaign against the court and sent shockwaves throughout the Australian legal fraternity, was an extreme example of a such man.

Engrossed in a bitter feud with ex-wife and bent on revenge, Warwick targeted judges who presided over his matters and other people associated with the court, shooting dead two people and killing two more in bombing attacks.

His reign of terror lasted from 1980 to 1985 yet Warwick was only convicted following two inquests and a three-decade long police investigation.

He was sentenced to life in jail without parole in September 2020, decades after gunning down Justice David Opas, detonating the bomb that killed the wife of Justice Ray Watson and bombing a church, killing Jehovah's Witness minister Graham Wykes.

Judge Richard Gee, who took on Justice Opas' cases, escaped with his life when Warwick exploded a bomb at his home in Belrose, on Sydney's north shore, in March 1984.

Lawyers and judges lived in fear as Warwick evaded justice until his arrest in 2015, Ms Bryant says.

He died in jail in February 2025, aged 78.

Despite the Parramatta registry of the Family Court also being bombed in the dead of night in April 1984, staff turned up to work the next day to collect and move files to ensure minimal interruption to people's cases.

"It was a really amazing effort in the face of tragedy," Ms Bryant says.

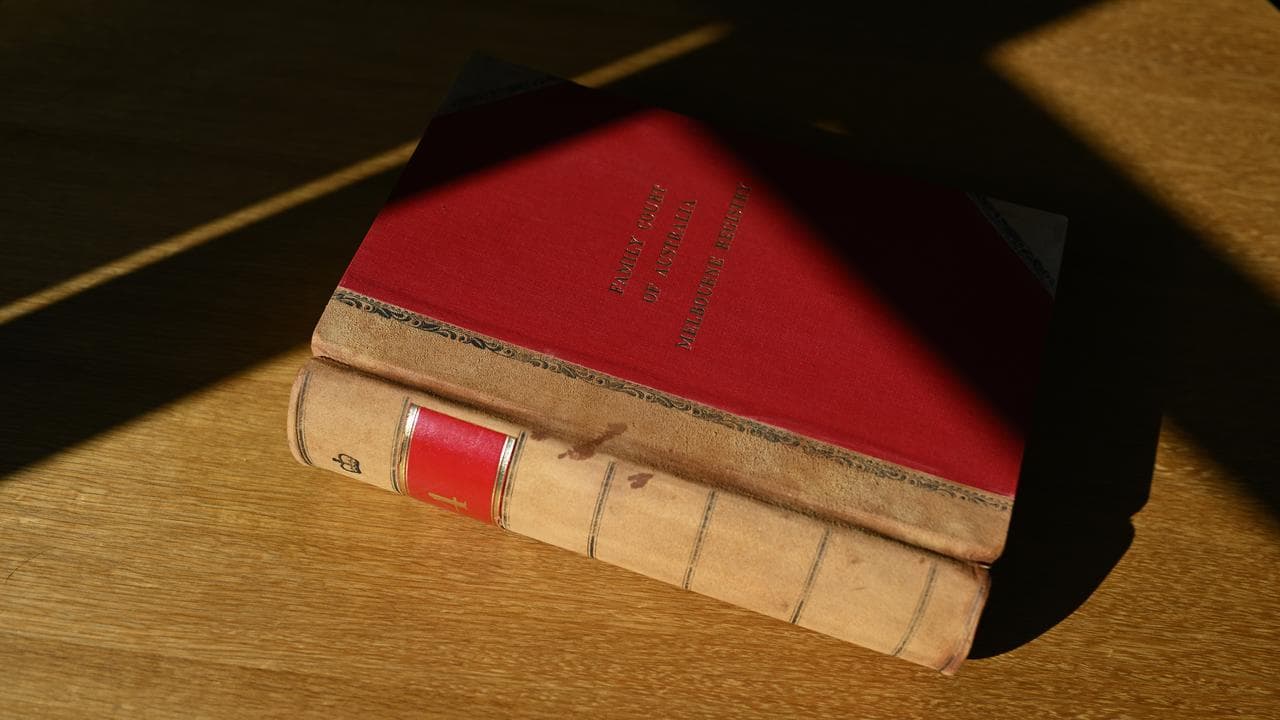

A ceremonial sitting took place at the Federal Circuit and Family Court in Melbourne on Friday to mark the family court's 50-year anniversary.

Chief Justice Will Alstergren told the gathering Gough Whitlam and the originators of the court would look at its legacy with pride.

"To see the court thrive as a superior court of record over 50 years is quite remarkable," he said.

"Although often shrouded in controversy because of the emotive nature of the work, it has always been a world-leading and innovative court with judges who are incredibly committed to dispensing justice in the best interests of the child."

The family court has supported over 5 million Australian families in some of their darkest times, Judge Alstergren added.

The court's first chief justice and eminent reformist, Elizabeth Evatt, said morale was strong in the building despite the challenges.

"Everyone that worked in the Family Court, all of the judges appointed to the court, they were all highly committed to the principles of the Act and the services to help people resolve their disputes," she said.

Ms Bryant championed Ms Evatt's work in establishing the court in 1976.

"She was the first chief justice, which in those days, having a woman as a head of jurisdiction was completely unknown," she says.

"She had to set up a court, and she had to deal with a new Act. She did a terrific job and her legacy is very much still evident in the court today."

A significant decision Ms Bryant presided over was Re Jamie, a case authorising parents to prescribe children puberty blockers to children without the court's consent.

The 2013 case involved a 10-year-old boy who had long identified as a girl and was well advanced in puberty, with the decision hailed as a human rights victory.

It was heralded as a shift in the fight for access to gender-affirming care and is still discussed today.

As the traditional nuclear family became less common and superannuation was introduced, property matters before the Family Court also became more complex, Ms Bryant says.

"When we started out, nobody had superannuation and by the time I finished, everybody had it," she says.

"Women also came to work as much as men, all sorts of tax reforms kicked in, people set up company structures to minimise tax - unravelling all of that became more complicated."