There are two ways to fix Australia's inflation problem, a leading economist for a top bank says.

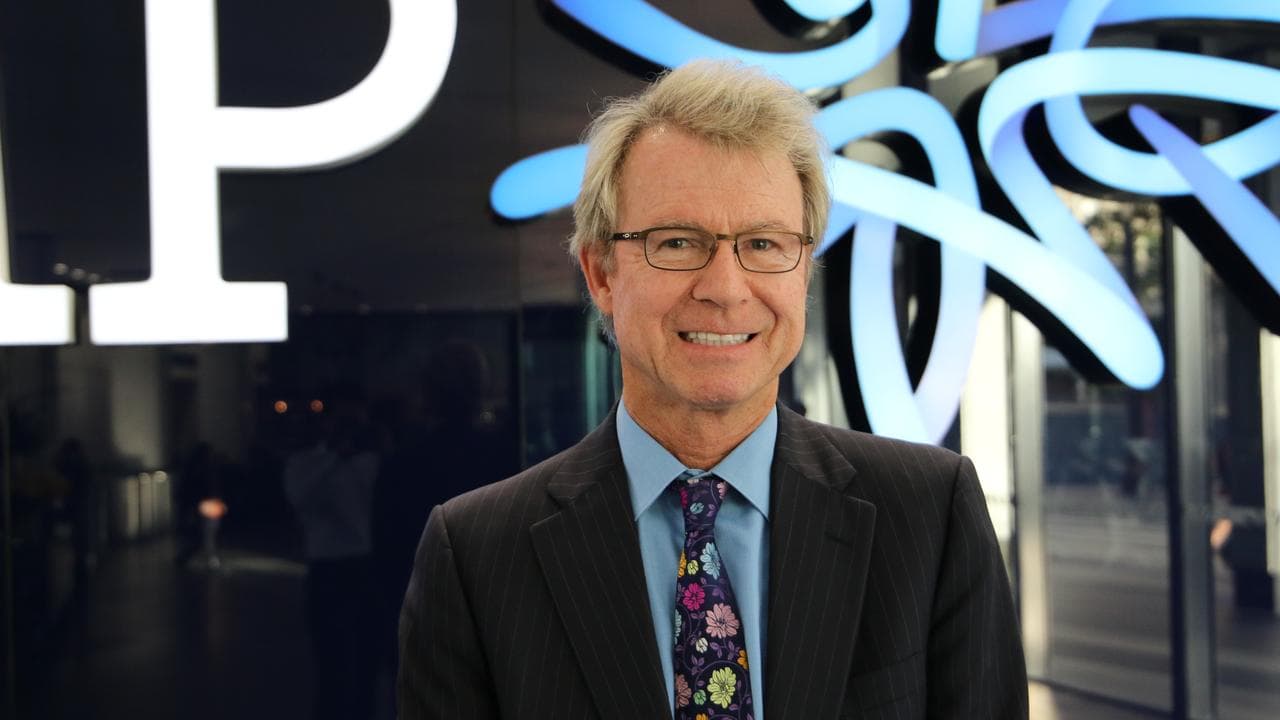

One, HSBC chief economist Paul Bloxham, says is to restrain government spending, allowing for the private sector to continue its recent upsurge without pushing price growth even higher.

The other is for the Reserve Bank to hike interest rates, adding thousands of dollars a year in living costs for mortgage holders and constraining the recovery in private investment.

Treasurer Jim Chalmers on Wednesday chose not to select option one, so Australians will have to settle for option two.

"As public spending has continued to remain strong, and the projections for its slowdown look ambitious, we expect the RBA will need to lift its cash rate in 2026," Mr Bloxham said in a research note.

"In short, tighter fiscal policy could do the job instead of tighter monetary policy. Another way to put it is that a slowdown in public spending would make way for more private sector spending."

The mid-year budget update showed public spending is forecast to grow at 4.5 per cent this financial year, stronger than expected in the March budget.

But Dr Chalmers said the update meant smaller-than-expected deficits and less debt in each of the next four years.

That made it "the most responsible mid-year update on record".

Despite spending growth blowing out this year, Treasury's forecasts rely on a heroic assumption that the government will exercise extraordinary restraint down the track.

Spending growth is forecast to be at a near standstill 0.3 per cent next financial year, a substantial pullback in spending and the weakest growth in public payments in over a decade, Mr Bloxham said.

AMP chief economist Shane Oliver said public spending as a share of GDP is well above pre-pandemic levels, contributing to lower productivity, crowding out the private sector and adding fuel to an already overheating economy.

"All of which is making the RBA’s job in keeping inflation down harder and will, if the RBA has to raise rates next year, put more pressure on the private sector - particularly Australian households - to keep a lid on their spending," he said.

Then there's the spending the government has squirrelled away "off-budget".

The gap between cumulative headline deficits, which includes spending loosely classed as investments, and underlying deficits, which the government places greater emphasis on because they are smaller, has widened from $85 billion in March to $93.8 billion.

"Unfortunately, some of these expenses are not necessarily wise investments and may have to be written down in value – but they still add to federal debt," Dr Oliver said.