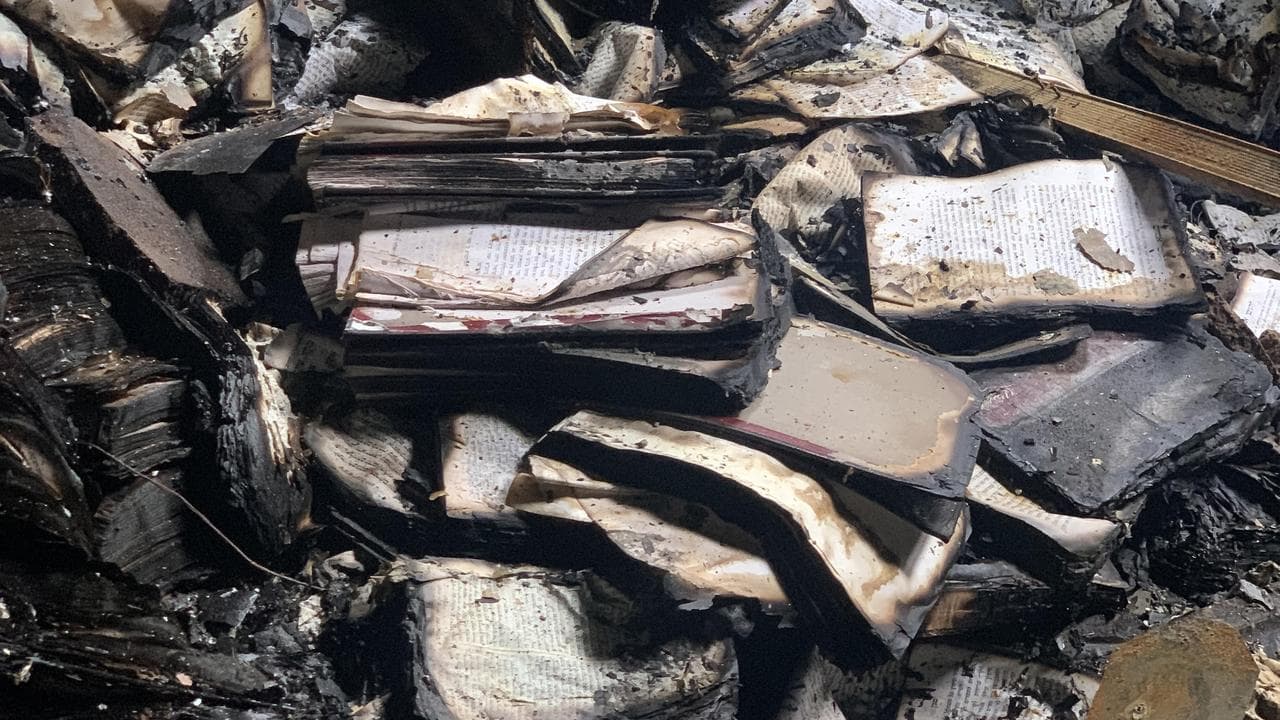

Within a few hours of a firebombing attack on a Melbourne synagogue, unverified claims about the incident were already rife on social media.

Some viral posts stated without evidence that pro-Gaza protesters or the “far left” were to blame.

Others claimed the fire might have been intentionally started by members of the Jewish community or Israeli Mossad agents, a so-called “false flag” event orchestrated to garner sympathy and cast suspicion on someone else.

Social media has fuelled the spread of misinformation following major incidents, particularly in the absence of established facts.

But experts say more can be done to stop unsubstantiated rumours taking hold.

“You’ve got to stop the voids in social media conversations,” said Anne Kruger, a journalist and University of Queensland academic who specialises in tackling misinformation.

Humans need answers, Dr Kruger told AAP, and information voids are immediately filled “by whatever is available”.

“That’s where the misinformation can take hold,” she said.

“We’re really susceptible in these moments to misinformation and disinformation, and we need to be really aware of that.”

Dr Kruger pointed to April’s deadly knife attack at a Bondi Junction shopping centre as an example of where the rush to fill the information gap can go badly wrong.

Shortly after the incident, some social media accounts shared an unverified claim that the killer was a Sydney student of Jewish heritage.

The false claims were subsequently reported as fact, even by some mainstream media.

By the time police confirmed 40-year-old Joel Cauchi as the attacker, the student's name was trending on social media and the misidentified 20-year-old had been subjected to a torrent of online abuse.

Much of the abuse drew attention to the student’s Jewish heritage and used anti-Semitic language.

Dr Kruger said she was unsurprised when she saw some of the names spreading the rumour: “Of course they would do that. That totally fits their agenda and their ideology.”

Journalists in particular, she said, needed to be more aware of misinformation spreading online and the tactics used to push ideologically-driven narratives into the mainstream.

Dr Kruger also wants to see compulsory media literacy training in schools and more government funding for public interest journalism.

Other experts are focusing on a bottom-up solution to Australia’s misinformation problem.

The University of Melbourne's Centre for Cities has brought together academics and local government officials to discuss the most effective ways to stop misinformation spreading in the community.

In 2024, the centre published the Disinformation in the City report urging local authorities to take a proactive approach to challenging misinformation.

The report’s lead author, Ika Trijsburg, told AAP the first step is understanding where people get their information.

Publishing a statement on a government website or Facebook page is no longer enough, she said.

“If there are certain groups that are only really accessing this kind of information through WhatsApp groups, make sure you have a way to get the information into those WhatsApp groups.”

Religious communities can also play a role in tackling false rumours, Ms Trijsburg said, because they are highly trusted by the people in those communities and already have mechanisms for disseminating information.

Ms Trijsburg said the tone of the message is also important because negative language can lead people to disconnect, whereas positive messages can help inspire collective action.