Internet users dubbed it the dope pope: viral images of 86-year-old Pope Francis wearing an oversized puffer jacket you might expect on a rap artist.

But details around the pontiff’s fingers, which seemed to merge with a coffee cup, tipped many off to its artificially intelligent origins.

Almost two years later, the same cannot be said for a growing number of realistic and compelling AI-generated videos promising to show everything from political coups and international arrests to achingly cute cats and celebrity endorsements.

A recent demonstration of one AI video tool imitating the cast of Stranger Things won more than 17 million views on social media and hundreds of shocked responses.

Experts say AI technology is advancing so rapidly fake videos will soon become indiscernible from real ones and the controls that promise to warn viewers about their provenance remain years from launch.

Advances in artificial intelligence technology have accelerated since OpenAi launched ChatGPT in late 2022, triggering a gold rush in the industry.

The company inspired a similar revolution with its Sora 2 video tool, AAP FactCheck editor Ben James says, both in terms of the quality of its output and its ease of use.

“These videos are ultra realistic and can be produced with just a few prompts,” he says.

“A few years ago, creating this kind of content would have required professional visual artists and expensive software.”

The AI tool can create videos for users based on text descriptions and details such as the time of day, the type of subject, dialogue, style and ambience.

While Sora 2 has yet to be launched in Australia, other AI video tools are available, such as Google’s Veo 3 and Runway Gen-4, and many of the clips they create are making an impact.

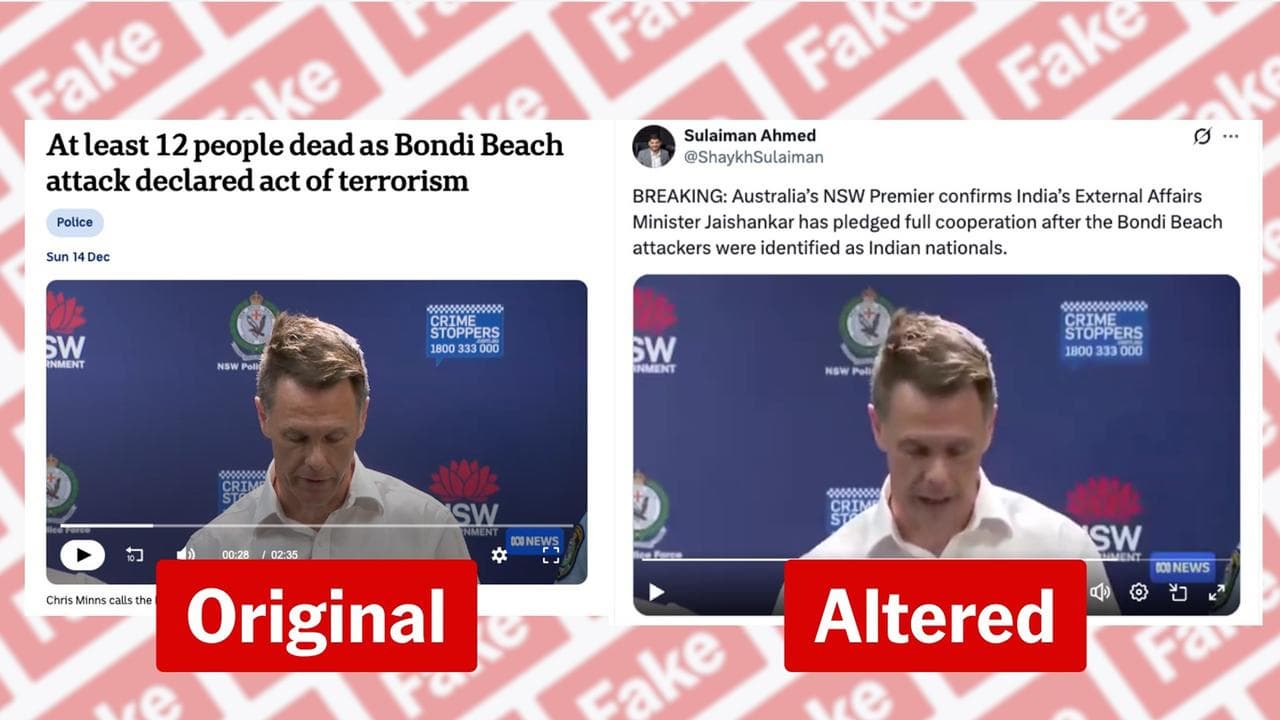

AI-generated videos purporting to be body-cam footage of former Venezuelan president Nicolas Maduro’s arrest recently appeared on Instagram and TikTok, for example, while a Facebook video falsely claimed to show soldiers storming Spanish congress.

Researchers debunked both videos using watermarks hidden in their metadata, Mr James says, but their origins would not be apparent to everyone.

“As soon as platforms like Sora 2 introduced visible watermarks, others began developing tools to remove them,” he says.

“That’s why invisible watermarks are vitally important to our work. They may not be immediately obvious and most users won’t encounter them directly, but they can’t easily be removed.”

Mandatory watermarking for AI-generated images and videos has long been requested by people in the technology, legal and creative fields, RMIT University's Centre for Human-AI Information Environments director Lisa Given says, even though a consensus about them has yet to be reached.

“Thinking about the Pope and the puffy coat, the New York Times immediately started labelling things as AI-generated to be really clear with readers at that time,“ she says.

“They’ve continued with that practice but those kinds of practices are not mandated, they’re not really embedded as an expectation.”

Deepfake videos can pose significant harm to viewers if they are designed to deceive, she says, particularly in fields such as health and employment.

While the federal government consulted the public on mandatory guardrails for AI technology, its National AI Plan, released in December, backed away from specific laws governing the technology.

While the issue is a global one, Prof Given says, local regulations could help to address its most pervasive threats.

“I was quite hopeful when the government was originally saying that for high-risk uses of AI there would be tighter regulation,” she says.

“The minute you get into areas of misinformation and especially disinformation... the stakes become much higher and the potential that people will be harmed by that are greater.”

Worldwide efforts are being made to identify AI-created content, such as Adobe’s Content Authenticity Initiative that has signed up more than 3300 members.

Within five years, an industry labelling standard will mark all artificially generated content, UNSW AI Institute chief scientist Toby Walsh predicts, and will be embedded in hardware and software.

The technology could do for AI warnings, he says, what digital certificates did for online security.

“Every device, every browser, is going to put check marks up for you - it will look at the metadata and tell you whether it’s AI-generated, AI-manipulated or not,” he tells AAP.

“The problem is it’s not in the fabric of the internet now.”

While internet users wait for standards to catch up, Prof Walsh says, they should carefully scrutinise what they see online, not just counting a subject's fingers but looking at who posted the content and considering their motivations.

“It is concerning because we can’t unseen the things that we’ve seen,” he says.

“We’re used to believing the things we see are true and we’re not longer in that world anymore.”